TL;DR

- India’s ancient philosophical frameworks—Ṛta, Dharma, Pañcabhūta, Ahimsa, and Aparigraha—offer time-tested principles for sustainable fashion that predate Western sustainability models by millennia

- Traditional practices like khadi production, natural dyeing, and zero-waste garment construction demonstrate IKS in action, supporting 4.3 million handloom weavers across India

- IKS-based fashion addresses root causes (overconsumption, ecological harm) rather than symptoms, unlike many modern “sustainable” initiatives that still operate within extractive frameworks

- Fashion design students can integrate IKS through curriculum choices, project work, and positioning themselves in India’s growing ethical fashion economy

- National Education Policy 2020 mandates IKS integration, making this knowledge foundational rather than optional for Indian fashion education

Who This Article Is For: This comprehensive guide serves fashion design students, aspiring designers, educators, and sustainability-focused professionals seeking to understand how India’s ancient knowledge systems provide philosophical and practical frameworks for ethical fashion—knowledge now central to design education under NEP 2020.

The Crisis and the Opportunity

The global fashion industry produces 92 million tonnes of textile waste annually. It accounts for 10% of global carbon emissions and 20% of industrial wastewater pollution. Fast fashion has normalised buying garments worn fewer than five times before disposal.

But India has been doing sustainable fashion for thousands of years.

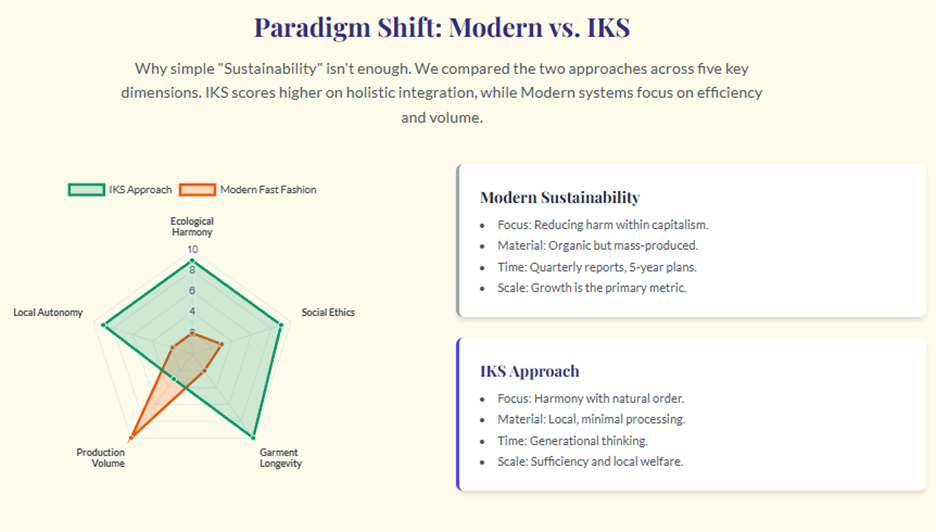

Long before “circular economy” became a corporate buzzword, Indian textile traditions practiced zero-waste pattern-making. Before “slow fashion” entered the lexicon, khadi production embodied patience, localisation, and artisan welfare. The numbers are worth pausing on: India’s handloom sector employs 4.3 million weavers, making it the second-largest employment provider after agriculture, whilst producing textiles that often last decades.

This isn’t about romanticising the past. It’s about recognising that India’s philosophical frameworks—collectively known as Indian Knowledge Systems (IKS)—offer sophisticated, time-tested approaches to fashion that address sustainability at its roots rather than merely treating symptoms.

With the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 mandating IKS integration across disciplines, fashion education in India now has an opportunity—and a responsibility—to position ancient wisdom not as nostalgic tradition but as foundational knowledge for contemporary design practice. Understanding the environmental impact of fast fashion makes this integration even more urgent.

What Are Indian Knowledge Systems in the Context of Fashion?

IKS encompasses philosophical, practical, and ethical frameworks derived from Indic traditions spanning Vedic thought, Ayurveda, traditional craft knowledge, and regional textile practices. When applied to fashion, these aren’t abstract concepts but actionable principles that have governed Indian textile production for millennia.

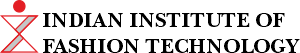

Frankly, this is where most sustainability discussions miss the point. Western sustainability frameworks often focus on mitigating harm within existing capitalist production models—using organic cotton whilst maintaining 52-season fast fashion cycles, for instance. IKS challenges the foundational assumptions: Why produce so much? What is fashion’s role in human life? How do we honour the earth’s resources and the hands that craft?

The philosophical depth here matters. IKS doesn’t just offer techniques (though those are valuable); it provides an entire cosmology of production and consumption that modern sustainable fashion is slowly rediscovering.

Core IKS Principles and Their Fashion Applications

Ṛta (ऋत): Cosmic Order and Natural Harmony

Philosophical Foundation

Ṛta represents cosmic order, natural law, and the inherent harmony of the universe. In Vedic thought, Ṛta governs the succession of seasons, the cycles of growth and decay, and the balance of ecosystems. To live in accordance with Ṛta is to align one’s actions with nature’s rhythms.

Fashion Application

In design terms, Ṛta translates to seasonal alignment, zero-waste pattern-making, and production cycles that respect natural fibre availability. A designer working within Ṛta doesn’t force cotton harvests three times a year or dye fabrics during water-scarce months.

Traditional Indian garments embody this principle structurally. The saree’s six-yard uncut drape, the dhoti’s rectangular construction, and kantha’s repurposing of old cloth into layered quilts—all demonstrate zero-waste design that works with fabric’s natural properties rather than against them.

Curriculum Relevance

Fashion programmes integrating IKS teach students to design within material constraints as a creative opportunity, not a limitation. Courses covering principles of fashion design now include modules on pattern efficiency and seasonal production planning aligned with natural cycles.

Dharma (धर्म): Ethical Duty and Righteous Action

Philosophical Foundation

Dharma encompasses moral duty, ethical responsibility, and righteous conduct. It’s contextual—a designer’s dharma differs from a wearer’s—but always emphasises responsibility toward others and the broader ecosystem.

Fashion Application

In practice, Dharma manifests as fair compensation for artisans, transparent supply chains, and consumer education. It asks: What is our duty to the weaver whose hands created this fabric? What responsibility do we bear as intermediaries between maker and wearer?

The handloom sector demonstrates this through organisations like the Khadi and Village Industries Commission (KVIC), which operates on cooperative models ensuring artisan welfare isn’t sacrificed for profit margins. The journey of Khadi itself is rooted in economic justice and self-reliance—Dharma applied to textile production.

Curriculum Relevance

Students in BSc in Fashion & Apparel Design programmes learn supply chain ethics, pricing structures that ensure artisan viability, and the legal frameworks governing craft protection (GI tags, intellectual property rights for traditional knowledge).

Pañcabhūta (पञ्चभूत): The Five Elements

Philosophical Foundation

Pañcabhūta—earth, water, fire, air, and space—represents the material composition of the universe. Indian philosophy emphasises balance among these elements and minimising disruption to their natural states.

Fashion Application

Textile production inherently involves all five elements: earth (fibres, dyes), water (processing), fire (energy), air (drying, oxidation in dyeing), and space (the conceptual element, representing design intention). IKS-aligned fashion minimises elemental harm—using plant-based dyes that don’t poison water sources, natural fibres that decompose, and air-drying over energy-intensive processes.

Natural dyeing traditions exemplify this balance. Indigo (Indigofera tinctoria), madder (Rubia cordifolia), and turmeric (Curcuma longa) create rich colours without synthetic chemicals, whilst dyeing processes using fermentation and oxidation work with elemental properties rather than overriding them through industrial chemistry.

Curriculum Relevance

Fashion design curricula incorporating IKS teach material science through an elemental lens, connecting the psychology of colours to natural dye chemistry and water stewardship in textile production.

Ahimsa (अहिंसा): Non-Violence

Philosophical Foundation

Ahimsa, most famously articulated in Jain and Buddhist traditions but present across Indian philosophical schools, means non-violence toward all living beings. It extends beyond physical harm to include psychological, economic, and ecological violence.

Fashion Application

In fashion, Ahimsa principles prohibit toxic chemical use that harms ecosystems and workers, exploitative labour practices, and production models that devastate natural habitats. It also questions animal-derived materials, though perspectives vary—traditional silk production remains debated within Ahimsa frameworks.

Brands like No Nasties demonstrate contemporary Ahimsa fashion: GOTS-certified organic cotton, non-toxic dyes, and fair-wage production that doesn’t exploit workers through piece-rate pressure systems.

Curriculum Relevance

Students learn to conduct ethical audits of materials and processes, understanding the violence embedded in conventional fashion—from pesticide exposure in cotton farming to the psychological toll of garment factory conditions.

Aparigraha (अपरिग्रह): Non-Possessiveness

Philosophical Foundation

Aparigraha means non-possessiveness or non-hoarding. It’s a principle of voluntary simplicity, valuing quality and sufficiency over accumulation.

Fashion Application

Here’s the thing: Aparigraha directly contradicts fast fashion’s business model, which depends on generating desire for constant newness. An Aparigraha approach values a well-made khadi kurta worn for years over dozens of disposable garments.

This principle manifests in durability-focused design, classic aesthetics over trend-chasing, and care practices that extend garment life. Traditional Indian garments were often designed to evolve with the wearer—sarees passed through generations, their borders repurposed into blouses, their worn centres becoming children’s clothes.

Curriculum Relevance

Fashion education programmes integrating this principle teach students to design for longevity, calculate true cost-per-wear, and create aesthetics that transcend seasonal trends—skills increasingly relevant as consumers question overconsumption.

For a deeper exploration of how these principles interconnect, see our detailed analysis of core IKS principles in fashion.

Traditional Practices: IKS in Action

Khadi and Handloom Ecosystems

Khadi production—hand-spinning and hand-weaving of cotton—embodies multiple IKS principles simultaneously. It’s decentralised (Ṛta), ensures artisan livelihoods (Dharma), uses minimal resources (Pañcabhūta), involves no mechanised violence to ecosystems (Ahimsa), and produces durable garments (Aparigraha).

The KVIC supports over 2.5 lakh artisans through the khadi model specifically (within the broader 4.3 million handloom ecosystem), whilst the MSME framework around handlooms creates supply chains that keep value within local communities. This isn’t boutique production—India’s handloom sector contributes approximately 15% to the country’s total cloth production.

Natural Dyeing Knowledge

Traditional Indian dyeing knowledge represents sophisticated chemistry developed over centuries. Artisans understood mordants, pH adjustments, and colour-fastness long before industrial chemistry formalised these concepts.

Indigo dyeing involves fermentation processes that require precise timing and environmental conditions—knowledge transmitted through generations in craft clusters like Bagru and Sanganer. Madder roots produce reds, turmeric creates yellows, and combinations yield an entire spectrum without synthetic pigments.

What’s interesting here is that these methods also support agricultural diversity. Dye plants often grow as companion crops, creating economic incentives to maintain diverse agricultural ecosystems rather than monocultures.

Zero-Waste Garment Construction

The saree’s genius lies in its uncut form—six yards of fabric that require no pattern wastage, adaptable to any body size, and culturally coded for different occasions through draping styles rather than separate garments. The dhoti follows similar logic.

Kantha work takes this further: old sarees layer into quilts through running stitches, transforming worn textiles into new functional items. No fabric scrap is too small to find use.

Craft Cluster Economics and GI Protection

India’s craft clusters—Banarasi weaving in Varanasi, Pochampally ikat in Telangana, Chanderi fabrics in Madhya Pradesh—represent localised knowledge economies protected by Geographical Indication (GI) tags. These legal frameworks recognise that certain textile knowledge belongs to specific communities and regions, preventing appropriation whilst supporting local economies.

The National Handloom Development Programme and Handloom Mark certification work to formalise and support these ecosystems, whilst the Samarth scheme focuses on skill development within traditional craft parameters.

IKS vs. Modern Sustainability: A Comparison

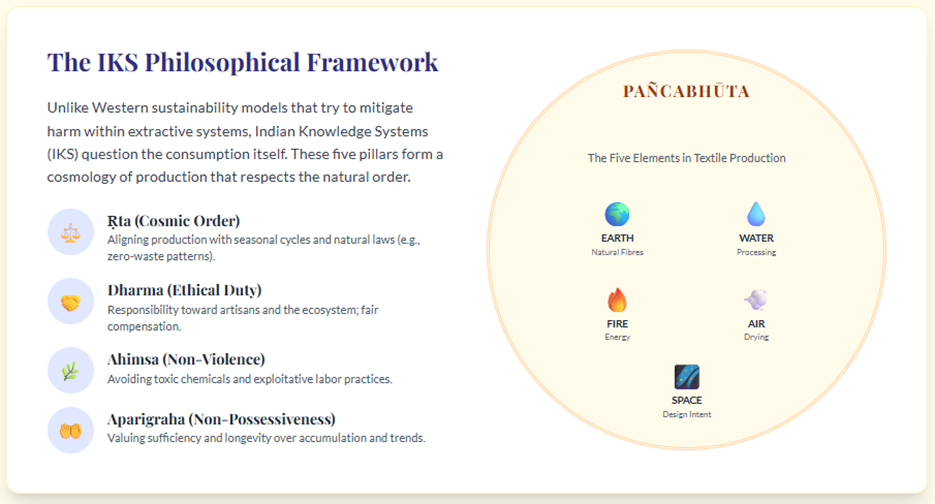

| Dimension | Modern Sustainability Frameworks | IKS Approach |

| Philosophical Basis | Reducing harm within capitalist production; carbon neutrality as goal | Questioning consumption itself; harmony with natural order as goal |

| Material Focus | Organic, recycled, or “eco-friendly” materials often within high-volume production | Natural materials with low processing, aligned with regional availability |

| Production Model | Sustainable factories with certifications (GOTS, Fair Trade) | Decentralised craft production; artisan-led rather than factory-based |

| Scale Assumptions | Scalability as success metric; growth-oriented | Sufficiency and local economies; growth questioned as goal |

| Time Horizon | Quarterly reports, 5-year sustainability plans | Generational thinking; techniques preserved across centuries |

| Innovation Approach | Technology-driven (lab-grown materials, recycling tech) | Technique refinement; working with rather than against natural properties |

The irony is that many “innovations” in sustainable fashion are rediscoveries of IKS principles—zero waste, natural dyes, slow production—repackaged with contemporary branding.

IKS in Practice: What Brands Are Actually Doing

Several Indian fashion enterprises demonstrate IKS principles in commercial practice:

Fabindia built a ₹1,000+ crore business around handloom products, directly sourcing from over 40,000 artisans across craft clusters. Their model demonstrates that IKS-based fashion can achieve scale whilst maintaining craft integrity.

Grassroot by Anita Dongre works with 1,200+ karigars (artisans) through sustainable livelihoods programmes, combining traditional embroidery techniques with contemporary design. Their model addresses both environmental sustainability and social equity—both Dharma considerations.

Raw Mango by Sanjay Garg revitalised interest in traditional weaving techniques amongst urban consumers by positioning handloom as luxury rather than merely ethical. This cultural reframing matters: IKS fashion doesn’t rely on guilt-based consumption but on intrinsic value.

Doodlage practices zero-waste design by creating collections entirely from factory surplus and deadstock, embodying both Aparigraha and Ṛta through working with available materials rather than creating new demand.

Government support through the National Handloom Development Programme, which allocated ₹738.44 crore (2017-2020), and the Handloom Mark certification demonstrates institutional recognition of these models’ viability.

Honest Challenges and Limitations

Production Scale and Speed

Handloom production is slow. A single Banarasi saree can take weeks to months, depending on complexity. This fundamentally limits scale in ways that don’t align with conventional retail models demanding high inventory turnover.

Cost Factors

Artisan-made garments cost more than mass-produced alternatives, creating accessibility challenges. Whilst true cost accounting—environmental degradation, social harm—makes fast fashion expensive in hidden ways, the upfront price difference remains a barrier.

Declining Artisan Populations

Weaver populations are aging, and younger generations often seek more stable, less physically demanding work. Despite government support, the handloom sector faces labour shortages that threaten knowledge transmission.

Market Perception Gaps

Traditional textiles sometimes carry “old-fashioned” associations that designers must overcome through contemporary aesthetic integration—a challenge that requires both design skill and cultural reframing.

Quality Inconsistency

Without industrial standardisation, handmade products show natural variation. This is philosophically aligned with Ṛta (no two natural objects are identical), but can create challenges in retail contexts expecting uniform products.

And that’s precisely the opportunity. Designers who can navigate these constraints whilst maintaining IKS integrity create genuinely alternative fashion systems rather than merely greenwashed versions of conventional models.

For Fashion Design Students: Applying IKS in Your Education

Curriculum Choices

Seek programmes offering modules in traditional textiles, natural dyeing, and handloom technology alongside contemporary design. IIFT Bangalore, for instance, integrates IKS principles within its fashion design courses, recognising that students need both traditional knowledge and contemporary market understanding.

Project Work

Design your major projects around IKS constraints: zero-waste patterns, natural dyes only, or collections created entirely from existing materials. These constraints force innovation.

Industry Connections

Intern with brands actively working with craft communities—understanding the economics and logistics of IKS-based fashion firsthand. Whether through Diploma in Fashion Design programmes or degree courses, seek opportunities to visit craft clusters.

Research and Documentation

Many traditional techniques risk disappearing. Student research documenting regional dyeing methods, weaving patterns, or embroidery techniques contributes to knowledge preservation whilst building expertise.

Positioning and Career Planning

India’s ethical fashion sector is growing, but it requires designers who understand both IKS frameworks and commercial viability. Position yourself at this intersection rather than choosing between tradition and market relevance.

Why IKS Matters for Fashion Education in India Today

India occupies a unique position globally: one of the world’s largest fashion markets, home to extraordinary craft traditions, and now implementing educational frameworks that mandate IKS integration.

The NEP 2020 explicitly requires IKS across disciplines, recognising these knowledge systems as foundational rather than optional cultural heritage. For fashion education, this means teaching sustainable design through indigenous frameworks rather than importing Western sustainability models wholesale.

The UGC’s emphasis on IKS research and pedagogy creates institutional support for this integration, but its success depends on fashion programmes genuinely engaging with philosophical depth rather than superficial cultural aesthetics.

These perspectives align with national education and skill-development frameworks, where IKS is positioned as foundational knowledge rather than an elective cultural add-on.

Globally, as fashion grapples with its sustainability crisis, India’s centuries-old practices offer tested alternatives. But frankly, this knowledge transfer shouldn’t flow one direction. Indian fashion education must claim IKS as contemporary design knowledge, not museum pieces.

Trust Note: Interpretations presented here are drawn from widely accepted Indian philosophical and textile traditions integrated into contemporary fashion education. The application of ancient principles to modern contexts involves considered interpretation that honours source traditions whilst addressing contemporary challenges.

Frequently Asked Questions

What does IKS mean in fashion design?

IKS (Indian Knowledge Systems) in fashion applies ancient Indian philosophical principles—Ṛta (cosmic harmony), Dharma (ethical duty), Ahimsa (non-violence), and Aparigraha (non-possessiveness)—to contemporary design. It encompasses traditional craft knowledge, sustainable materials, and production models prioritising ecological balance and artisan welfare over commercial growth.

How is IKS different from Western sustainable fashion approaches?

IKS questions consumption itself rather than merely reducing harm within existing production models. Whilst Western sustainability often focuses on eco-friendly materials or carbon-neutral factories within high-volume systems, IKS principles challenge the need for constant newness, prioritise decentralised artisan production, and work with natural cycles rather than against them.

Can IKS-based fashion be commercially viable?

Yes, but it requires different success metrics. Brands like Fabindia (₹1,000+ crore revenue) and Grassroot demonstrate commercial viability whilst maintaining artisan partnerships. However, IKS fashion prioritises sufficiency and quality over rapid scalability—a fundamentally different model from fast fashion economics.

What are examples of IKS principles in traditional Indian garments?

The saree’s six-yard uncut construction exemplifies zero-waste design aligned with Ṛta. Khadi production embodies Dharma through artisan welfare. Natural dyeing with indigo and madder demonstrates Ahimsa by avoiding toxic chemicals. Kantha’s repurposing of old textiles shows Aparigraha through non-possessive reuse.

How does NEP 2020 affect IKS in fashion education?

The National Education Policy 2020 mandates IKS integration across disciplines, positioning ancient knowledge systems as foundational rather than optional. For fashion programmes, this means incorporating traditional textile knowledge and sustainable practices rooted in Indian philosophy into core curricula.

Are natural dyes as durable as synthetic ones?

When properly processed with appropriate mordants, many natural dyes offer excellent colour-fastness. Indigo, madder, and certain barks produce particularly stable colours. Some natural dyes require more care in washing, and colour outcomes show natural variation—a different aesthetic philosophy embracing uniqueness over industrial uniformity.

What government schemes support IKS-based fashion in India?

Key initiatives include the National Handloom Development Programme (₹738.44 crore allocated 2017-2020), Handloom Mark certification, KVIC support for khadi artisans, and the Samarth scheme for skill development. GI tags protect region-specific techniques like Banarasi, Pochampally, and Chanderi weaving.

How can fashion students learn IKS-based design?

Seek programmes integrating traditional textile modules, natural dyeing workshops, and handloom technology alongside contemporary design training. Project work using IKS constraints forces innovation. Internships with craft-based brands provide practical understanding. Documenting traditional techniques through research builds expertise whilst contributing to knowledge preservation.

Does IKS fashion only work for traditional-looking clothes?

Not at all. Designers like Sanjay Garg (Raw Mango) create modern aesthetics using traditional techniques, whilst Doodlage produces urban streetwear through zero-waste principles. IKS provides frameworks and methods—design outcomes can be traditional or contemporary. It’s about production philosophy, not visual nostalgia.

What are the biggest challenges facing IKS-based fashion?

Honestly, scale remains difficult—handloom can’t match factory speeds. Cost gaps make artisan-made products less accessible upfront. Aging artisan populations threaten knowledge transmission. Market perceptions sometimes associate traditional textiles with outdated aesthetics. Quality variation in handmade goods conflicts with industrial standardisation expectations.

A Path Forward

IKS offers fashion education in India something rare: a philosophical framework for sustainability that emerges from within rather than being imported. It’s not perfect—the challenges are real—but it addresses fashion’s crisis at a deeper level than most contemporary approaches.

For students seeking fashion education that integrates sustainability principles with India’s textile heritage and philosophical traditions, exploring programmes with strong IKS integration and industry connections to sustainable fashion becomes a natural next step. Those interested can learn more about admissions to programmes incorporating these frameworks.

The question isn’t whether IKS belongs in modern fashion education. Under NEP 2020, it already does. The question is how deeply we’re willing to engage with its implications—both the wisdom and the inconvenient truths about consumption it reveals.